“A lack of cinema”: this is what director Tyler Taormina diagnoses as one of the main problems in contemporary filmmaking — not referring to the medium itself but the use of that medium to its most unique capacity.

The expansion of filmmaking’s technical possibilities has paradoxically led to an oversaturation of bland shot-reverse-shot coverage rendering mechanical screenplays. More of the same. Omnes Films, the production collective co-founded by Taormina alongside fellow Emerson College alums Jonathan Davies, Michael Basta, and Carson Lund, stands in contrast to such visually rote filmmaking. Their films, including Taormina’s three features (Ham on Rye, Happer’s Comet, and his new film Christmas Eve in Miller’s Point), abandon traditional narrative to capture sensations that are felt most tactilely through cinema: the way in which nighttime sets banal landscapes alight with possibility, the shifting beams of car headlights shining through suburban windows, or the magic that comes from being steeped in the textures and rituals of a world you don’t quite understand, where unspoken familial and social codes govern the slightest glance, often in a way that no character is even aware of….

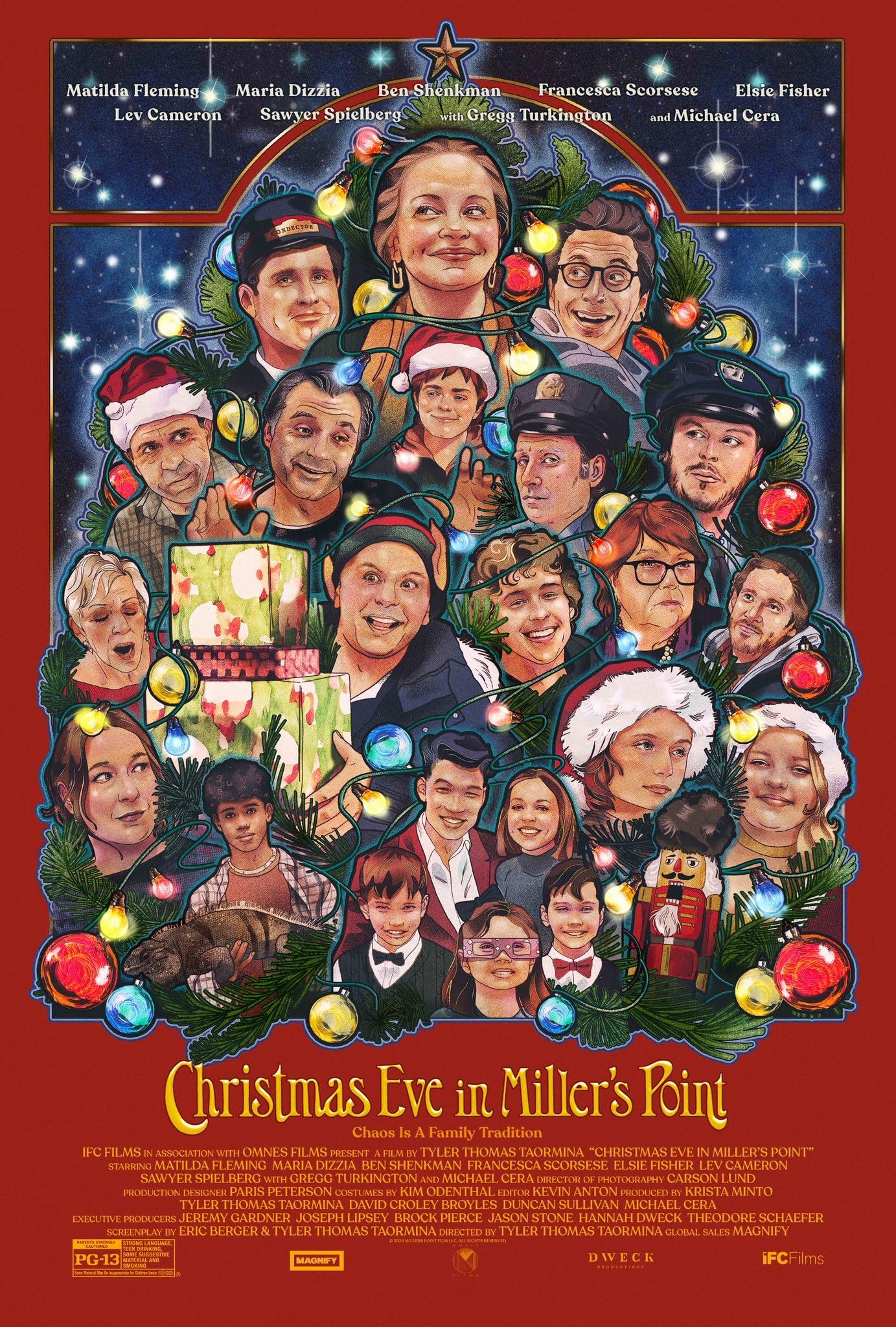

Taormina’s latest feature shows the Balsanos, a large Italian-American family, and their Christmas dinner in the declining grandmother’s soon-to-be-sold home. To render his memories of Christmas as a Long Island adolescent, Taormina alchemizes a disparate set of influences (from a Hou Hsiao-Hsien-esque floating camera to a Christmas Parade that recalls Scorsese’s editing as much as it does Coca Cola’s “Holidays Are Coming”) to create a cinema that defies the mold of any referent.

Earlier this year I spoke with Taormina about his influences, the methodology of translating memory to film, and his complicated relationship to suburban adolescence.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Talking about Omnes Films, what were the conversations you were having that led to the creation of the collective?

In college, [the other Omnes directors] made a film called “Omnes,” and I feel like there's that instinct of college students: “let’s make a production company for it.” I don't think it was very serious for their short films. And then when I came to them with Ham on Rye after we'd all become friends over the years, it got really serious. It was like, “we've been waiting to make features our entire lives and now it's before us.” So, we put the Omnes banner on it just to continue the dreaming that they had in college.

What really interested us at the formation of Omnes — which I will cite most officially around the time of the production of Ham on Rye — is that we knew we wanted to all bring our talents and minds together, because it wasn't just that one of us knew how to shoot well and one of us knew how to edit well, which was true — it was more that we all had a very shared sensibility. These ideas that I swear I couldn't put to words, we all just understood. Before Ham on Rye, I think that the rest of the gang really looked at making a feature as a “wait until the industry comes to you” thing. And that what Ham on Rye taught us and what it unlocked for us was that, “oh no, um, fuck that.” Let's just do it all ourselves in any way we possibly can.

Is that the method that you see yourself continuing with?

Really everything is project by project. And we've tried to approach the industry. It's just very hard to find a match within the Hollywood apparatus for the type of work that we do. And you can see the results there are primarily sterilized and anesthetized. There could be a project where we are collaborating within the beast, so to speak, but it would have to be on the terms that are comfortable for us, which obviously have to do not only with creative control, but with the production, as a family. It could happen — I don't want to close any doors, but it's been easier to find private equity to make these films so far.

So much of that working within the system can require putting a label on your work. And I feel like Omnes’ films can be talked about in terms of referents but they defy a specific kind of categorization.

Sure, sure. I would agree.

I wonder if that comes from a fusion of disparate influences. Watching Happer's Comet (2022), for example, I was thinking of Apichatpong and Chantal Akerman and films that fall into this high art category that seems almost incongruous with movies about the American suburbs, as if strip malls and parking lots are too disposable to warrant that more studied lens. But that influence is there, and you've also talked about the influence of Nickelodeon and 90s TV shows or movies like American Graffiti (1973). Do you view any kind of distinction between those influences?

Actually I do. I'm only speaking for myself here, but I grew up consuming the most vacuous and ridiculous movies and TV shows, music even. I really can't believe the things I was interested in when I was young and growing up in the suburbs, and that kind of expanded into my worldview in so many ways. For me there is a very distinct line between, let’s call them the John Hughes half and the Franco Piavoli* half of my influences. I think that the reason that I'm making these films is to reconcile with my past and coming of age into the Franco Piavoli [era], my mind expanding to those places. There’s a very abrasive meeting of these two parts of myself.

*director of Taormina’s favorite film, Voci nel Tempo (1996)

How do you feel like your view of that adolescent period when you liked that media has changed since going to college or moving to Los Angeles?

There's two ways to answer that. One is that I listened to misogynistic music; that was a big theme of a lot of the music that myself and all my friends, including women, listened to. And the movies I watched were really kind of bigoted. That was just where Hollywood was after 9/11. It was really a disgusting period for studio filmmaking, and a lot of those films I really liked. So there's this kind of disgust that I have, but at the same time these relics of art represent a truly carefree time where I wasn't thinking critically the same way — I wasn't suffering those same worldly woes. So there's an idyllic remembrance of that time and all those artifacts in the John Hughes section of my life. I don't want to say that they're just worthy of critique. So many of these things are so beautiful too. Taking John Hughes again, for example, he has his racist films like Sixteen Candles (1984), but he also has masterpieces that I think are totally palatable for my conscience today. So there's a criticism, but there is a true and earnest fondness as well, a real love that I have for that part of my life.

Your films seem to have this preoccupation with documenting suburban activities as rituals. And with rituals there comes a kind of conservatism. How do you value those rituals and what role did they play in your life growing up?

It's a little vague because there's a gamut. I think the ritual depicted in Ham on Rye is distinctly... bad. It's really oppressive and negative, but the one in [Christmas Eve] I think is very positive. And the one in Happer’s Comet, I don't even know what you would call that — maybe somewhere in between. But I feel like I should tell you the story of my sister's wedding, which took place last year, where I had this wild revelation about my own work on one of the happiest days of my life. It followed the wedding of one of my best friends. There is a delineation between my family, who are all still very much in the conservative suburbs in mind and in body, and my friends, who all left [that environment]. I noticed that at my friend's wedding, all the speeches were ironic and there was just a lack of magic in the way people were interacting with the ritual. We were all so happy for their marriage but I noticed that the ways in which we interacted with the ritual were very different at my friend's wedding versus my sister's, which was a much more conservative or traditional environment.

I have a consciousness and analysis of these rituals that I think actually hinders a sense of grace that could be found in letting these rituals just be –– it's like the allegory of the cave, letting the codes and the steps that one must take just be, partaking in them without thought, whereas my mind isn't like that. I think it's somewhat a burden, but it's one that I wish to have, because now that I know so many of the issues with conserving these traditions, I know too much. So I think the rituals for me have been a look at this burden of consciousness.

Do you feel like filmmaking is a way for you to recapture the magic of those rituals or those experiences in a way that you can't quite feel directly?

In the case of Christmas Eve 100 percent. There's a romantic gap that time creates and it makes something very wondrous of the past, something very beautiful and shiny. There's also such a longing that comes with that phenomenon. I feel like art, specifically in my case filmmaking, is an incredible way of accessing — maybe not accessing, but animating or making an abstract phenomenon into a solid that can fit into my hand. That's what it feels like, and that's been a goal of mine for a very long time.

I think there's this desire to contain something that is always linked to film. It's in the word itself: “capture” on film.

Sure. Absolutely.

There's a capturing of the past that happens in your films, but what stands out to me is that they don't take place in a set past. They’re more an amalgamation of a whole post-war history. In Happer's Comet, for example, you see an iPhone and it almost feels anachronistic, even though the movie’s not literally set in the past, but it recalls it in so many ways through familiar images. You said in another interview that you were obsessed with aging. Is there a connection between that obsession, as well in Christmas Eve in Miller's Point showing this family at different stages of life — and this lack of a set period in your films?

It's something I never thought of… I'm just gonna give you my instinct but I feel like they do separate things. The vast ensembles really are a way in which I like to explore [different] ages, and the ambiguous time period is an experience of the impressions that things leave on me. It's like the emotional substrate of the past, whereas I think that the characters are more intellectualized in their differences. One of them is a thoughtless emotion and [the other] is very strategically rendered. You can almost think of them as a left foot and a right foot.

When you're conceiving these films or when you're writing them with Eric Berger, are you two very analytical about it? Are you thinking in terms of what you were talking about in the last question, like, “this character represents a certain state of being” or is it more intuitive?

I think it's a bit intuitive, and one of the ways we arrived at this film was through a real curiosity. You can imagine our creativity as a sentient being. We created this house and we wanted to look into every room and behind every couch and every corner and see what life was roaming about. And that led to us finding people of all ages, exploring in a sort of grid, and then pronouncing the characters… and then it became a little more intellectualized. We saw these characters as opportunities to explore phases of life. Obviously it's not as simple as that; it's not like everyone of a certain age bracket is the same character in this film, but I think that's a big starting point for the movie. We really try to create and explore gradients in every direction while we create these ensemble pieces. It might start out intuitively. At some point, I think it has to become intellectualized, but maybe only to a point. You kind of let the actors fill in the rest, or the Production Designer, for that matter. Our big exploration was the rooms; all these rooms in this house really do represent a lot of different parts of life. That's something we realized by putting the piece together.

How long did you spend in pre-production for Christmas Eve?

About six months. I really enjoy a long prep. I think it's really important for making small-budgeted films — I guess this is relatively a small-budgeted film but we were really punching way above our weight for the scale versus the ambition, so you really rectify that through the pre-production.

Did it having a bigger budget than Happer's Comet and Ham on Rye affect the vision a lot?

It didn't affect our intentions. I mean, it made an enormous difference in terms of the production. I never had celebrities on my sets before that. That changes a lot, not even because of them — these were the nicest people and I consider them all friends, but even still, you just have to have your shit together so much more. The machine needs to be so much more well-oiled when you're dealing with all these plates spinning. It actually felt like I hadn’t even produced a film before making this; it felt like learning from scratch. It was a rude awakening even though it went very well. But I wouldn't say my creativity was hindered or limited or even guided, I just gave myself as much room to dream it up as I could and I can't even think of any concessions that I made in the process.

What was the difference between conversations that you had with, say [cinematographer] Carson Lund over the look of Ham on Rye and what your working relationship was on this? Do you think it's evolved?

It's so hard to answer that. I feel like we have both evolved incredibly but our relationship feels exactly the same. We don't really over-talk any of this out. There's a few things mentioned, like “Oh, it's kind of like this movie,” and in this case, I suppose it's been well documented by now but we talked about the Coca-Cola ads from the fifties and Douglas Sirk and Home Alone (1990) and Vincent Minnelli. And after that I think he just understands exactly what I mean and vice versa. We go over the storyboards together. I write up storyboards. We go through every shot. We both don't remember [everything], but in the process of doing so, we solidify a lot of the conscientiousness about the vision, and then on set we don't look at it, we just shot-write on set.

So there is that room to create in the moment even with the planning?

There's guidelines. After we go through the storyboard then I put it to actual shots and we put them on paper and the AD is gonna be guiding us to meet what we had planned. But it's still open. A lot of times in Christmas Eve, we made our schedule because we [said], “what if it was in one shot?” We really thought about how to construct the scenes as economically as possible. There's intentions that may create a good framework for the production and there's a fluidity that needs to be there as well.

You use ethnographic to describe Christmas Eve in Miller's Point. I remember when my friend and I saw it, he described it as an anthropological film about Italian-American or “ethnic white” families. Was that very much part of the intention?

I mean, I'm not trying to be like Frederick Wiseman and keep a document for posterity, but it's a story of my life and my family. I think you can call all the rest of the Omnes films anthropological and ethnographic. And this one just happens to be about my family. But in the other Omnes films, one of them takes place in Venezuela [Lorena Alvarado’s Los Capítulos Perdidos (2024)]. One of them in Florida [Alexandra Simpson’s No Sleep Till (2024)], which is a lot more diverse than Smithtown where I grew up. It's making these sort of memory films…

We've been talking about words and the articulation of your ideas. It's interesting that in your films the dialogue very often seems like another layer of texture rather than something to be decoded the way that one might in a traditional narrative movie. Watching Christmas Eve (maybe just because of Gregg Turkington’s presence) it reminded me of Neil Hamburger's stand-up routines.

I think there's a lot of double play and hopefully even triple play going on [in the dialogue], where the texture approach is definitely part of our ethnographic, fly-on-the-wall approach, but we were thinking of this as a home movie made with the grammar of a sophisticated classic Hollywood film. So there needs to be truth in the words spoken, the kind of truth where if someone brings up a plot point, suddenly the dialogue betrays the sense of truth and becomes less human in a sense. That's how I feel in movies when the characters are servicing a plot and not a reality, but at the same time you have to do both, especially in a film like this where we have a lot of arcs and there's a lot of goals the film has to achieve. I think the challenge is creating that truth and those textures along with hitting certain marks that are completely necessary, like a lot of the uncles’ dialogue is actually about about these cultural elements that mean a lot to the film not just because “We need to know what this family thinks about the police,” but it actually plays into the plot where the police characters weigh into the whole equation. So it's a delicate dance to achieve both, to have an agenda and to just see truth play out. I can't say I have it on the forefront of my conscious brain but it definitely takes place in my body telling me, “Oh, that was wrong. False. Don't do that.”

It has to work within a structure without feeling too schematic, too mechanical…

Yeah, and there's a lot of tricks, like in film school I was taught that if you want to have expository dialogue, have the characters argue.

Since you bring that up, just out of curiosity, what was the film program at Emerson like when you were there?

I studied screenwriting. I didn't make any films in college, and I took a history of film class and a film theory class. It wasn't even film theory. It was like media theory. I loved it, though. I thought I had a great education. The film school was less an art school and more of a trade school. I wasn't surrounded by people who were trying to outdo each other with their knowledge of Béla Tarr or whatever. It was a lot more of a basic crowd. But then on the margins, we were able to sniff each other out. That's how Omnes was formed.

If you could diagnose a main problem with the current state of filmmaking, especially independent filmmaking, what would it be?

There is really a lack of cinema, honestly, in movies. So I really effort myself to just love this art form as much as I possibly can. Also, I feel like people don't really bleed for their films anymore. It costs an arm and a leg to make a film. It sucks. But I still feel like we're not in those days anymore where to shoot and edit on celluloid, I feel like only the most insane people came up from the independent realms doing so, and you see in their films they would die [for their art], you know.It seems like since the days of John Cassavetes mortgaging his house to make a movie… maybe the urgency behind making a film isn’t there as much.

Yeah, I heard a story about Jacques Doniol-Valcroze, one of the heads of Cahiers du Cinema back in the day. He was close with the people he hired such as Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, and there was a moment where Truffaut — I don't know if this is true but it really does exercise the point — as a critic slammed one of Jacques' films and it mattered so much to him that it drove him to the hospital. I feel like the stakes were so much bigger then and maybe that's because a lot more people were paying attention.

I read Richard Brody's Godard biography recently, and the way in which the people in the Cahiers took film seriously — they were ending friendships over it. It was something to live or die for.

Oh, absolutely. And when Truffaut or Godard would make a film, the other would be stricken with jealousy. Just not okay. Unwell.

Christmas Eve in Miller’s Point is now streaming on AMC+